The Society was inaugurated in 2001 and closed in 2017. It published regular newsletters, many containing valuable short articles on Bloomfield’s life, poetry and legacy. These are presented in chronological order below.

Society officers

President: Ronald Blythe

Academic Advisors:

Professor John Barrell

Professor John Lucas

Chair: Bridget Keegan

Vice-Chair: Simon White

Secretary: Philip Hoskins

Treasurer and Membership Secretary: Tim Burke

Newsletter Editor: John Goodridge

Website Editor: Simon Kövesi

Events Officer: Rodney Lines

North American Representative: William Christmas

Education Officer: Sam Ward

Hugh Underhill

Society Members

Olive Baldwin & Thelma Wilson, Brentwood, Essex

B. C. Bloomfield, Ashford, Kent

John Edward Bloomfield, Brockenhurst, Hants.

Mr & Mrs P. J. H. Bloomfield, North Walsham, Norfolk

Ronald Blythe, Wormingford, Colchester

Tim Burke & Siobhan Holland, Twickenham

Richard Burleigh, Charmouth, Dorset John

Edward Caves, Bedford

Patricia & Malcolm Chisholm, Peterborough, Cambs.

Bill Christmas, San Francisco

David Cobb, Braintree, Essex

Michael Cooper, Kirbymoorside, North Yorkshire

C. W. Cox , Saxmundham, Suffolk

Alan Cudmore, Stevenage, Herts

William A. Crane, Peterborough, Cambs.

Tim Fulford, Nottingham

Gill Goodridge, Lancaster

John Goodridge & Alison Ramsden, Nottingham

Bruce Graver, Hanover, New Hampshire

Paul Green, Peterborough, Cambs.

Allan and Nina Grove, Kidderminster, Worcs.

Patrick John Harrison, Shaftesbury, Dorset

Philip Hoskins, Shefford

Leonard & Cherill Illingworth, Evesham, Worcs.

Bob & Sandra Jarvis, Shalford, Surrey

Bridget Keegan, Omaha, Nebraska

Rodney & Pauline Lines, Spalding, Lincs.

Eric Lovegrove, Colchester, Essex

John Lucas, Beeston, Nottingham

Jonathan R. Miller, Keswick, Cumbria

Peter C. Mitchell, Weston-super-Mare, Somerset

Peter Moyse, Helpston, Peterborough

Nottingham Trent University, Library and Information Services

Michael Powell, Los Angeles, California

Simon Sanada, Toyohashi, Japan

Daphne Sayed, Horley, Surrey

Hugh Underhill, Bedford

Malcolm G. Wallis, Bletsoe, Beds.

Sam Ward, Exmouth, Devon

Richard Webb, Rotherham, Yorkshire

Simon White, York

Margaret Wimble, Herne Hill, London

Brian Winder, St. Albans. Herts.

Brian Winters, Uffington, Stamford. Lincs.

David C Woodward, Beccies, Suffolk.

Newsletter No. 1, June 2001

First things first; welcome to the Robert Bloomfield Society. Our fledgling organisation aims to bring together all those who admire Bloomfield’s poetry and prose, and we shall be organising regular events each year to bring our members together and advance the study of Bloomfield, his historical context, and the traditions of autodidactic, rural and local verse that he exemplified. The purpose of this Newsletter is to provide details and reports of our activities, act as a forum for discussion and information exchange, and publish new material on Bloomfield, I hope that we shall publish a variety of responses to Bloomfield here, including (but not restricted to) scholarly ones. The style will be; as far as possible; informal and accessible. Contributions from members will be gratefully received. They may include articles, notes, questions, thoughts, personal and creative responses, illustrations, and useful information of all kinds. This is, to change my metaphor, a small acorn. Please nurture it, and help it to grow into a large, and preferably sturdy and useful oak. I shall endeavour to make sure that it gets printed and distributed, and write what I hope will be the gradually diminishing in-between bits around other peoples’ contributions – I am grateful to Philip Hoskins and Sam Ward for their contributions to this inaugural number of the newsletter.

John Goodridge (editor)

NEWS AND INFORMATION

Bloomfield bicentenary activities and events

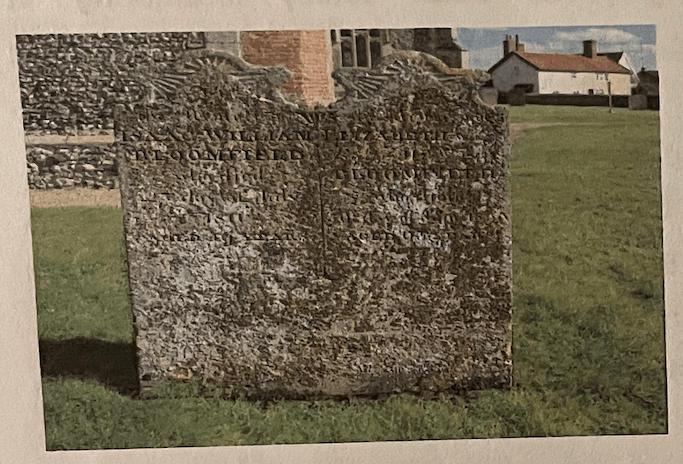

The launch of the Robert Bloomfield Society was the outcome of various individuals’ attempts to mark the two-hundredth birthday of Bloomfield’s most successful poem The Farmer’s Boy, which was first published on 1 March 1800. John Lucas and I published our Robert Bloomfield: Selected Poems (Nottingham: Trent Editions) in 1998, ahead of the bicentenary. On 1 March 2000 Philip Hoskins hosted a church service ceremony at Campton, Bedfordshire, where Bloomfield is buried, to commemorate the bicentenary. This was followed up by an exhibition on ‘Robert Bloomfield, Shefford Millennium Poet’ at nearby Shefford library in November.

On 24 June Bloomfield was the subject of a day seminar at the University of York, entitled ‘The “Peasant” Poet: A Symposium’, with papers from John Barrell, Tim Burke, Tim Fulford, Mina Gorji, Donna Landry, Simon White and myself. This was a pleasant and interesting day, and I am delighted that Simon White is now putting together a book of essays based on the seminar, with additional contributions from John Lucas and one or two others, I’m sure there will be more on this project in the next Newsletter.

Encouraged by the success of this event, we launched the Robert Bloomfield Society – long mooted – at a gathering of about thirty people at the Nottingham Trent university on 10 October. A display of Nottingham Trent’s recently acquired collection of early Bloomfield editions, including a rare presentation copy of the two volume Remains and several other notable copies, attracted interest, Ronald Blythe opened the proceedings with a thoughtful introduction to Bloomfield, writer to writer. After refreshments, there followed a number of readings from Bloomfield’s poetry and prose by Bloomfield enthusiasts, including the poet Mahendra Solanki. The event concluded with a business meeting at which we set up a steering committee to get things going.

In further recognition of the bicentenary, Bloomfield will be the focus of the John Clare Society of North America’s annual panel at the Modern Languages Association (MLA) convention in New Orleans in December 2001. And as we begin to plan our activities as a new literary society, there be further Bloomfield celebrations as the bicentenaries of Bloomfield’s other volumes come round, starting with Rural Tales, whose bicentenary falls in 2002.

Finally, in April 2001 there was an item on Bloomfield in the Anglia TV programme ‘Dead Interesting Peoples, programme which combs the graveyards of East Anglia in search of (you guessed it) dead interesting people. have some video copies of this if anyone missed it and would like to see it.

Forthcoming events

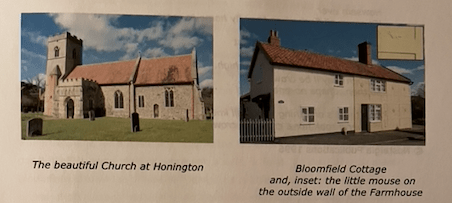

The Robert Bloomfield Society’s first event will be a coach trip round ‘Bloomfield Country’ in Suffolk, led by the author Ronald Blythe and organised by Rodney Lines. This will be held on Wednesday 19 September 2001. We shall meet at midday in Bury St. Edmunds, and visit the Moyses Hall Museum at (which holds ‘Bloomfield’s table’ among other things). Following a picnic or pub lunch we shall travel by coach round the villages associated with Bloomfield: Sapiston, Troston, passing Barnack Water, and Bloomfield’s birthplace at Honington, where we shall have some readings in the church.

We hope to hold our first, necessarily brief, General Meeting as a Society during this event. I am enclosing with this newsletter a draft constitution for the Society, and would welcome comments and suggestions on this either in advance of, or at this meeting.

We shall also be holding a seminar on Bloomfield in November at the Nottingham Trent University. Details of this will be in the next Newsletter. It is our intention to hold at least two events a year in the UK, one of which will be social rather than academic. Suggestions for possible future events will be very welcome.

NOTES AND ARTICLES

Constance’s Edwardian Legacy

With the apt motto floreat ager (may the field bloom) the (first) Robert Bloomfield Society was launched on 4 May 1904 on the occasion of the unveiling of a memorial at the poet’s house in Shefford commemorating his death in 1823. Dedication and admiration for Bloomfield’s work glowed in the prospectus for the society produced by its founding (and only recorded) president Miss Constance Isherwood, a strong-minded rector’s daughter from the adjoining village of Meppershall.

The demands on members were unequivocal. They were expected for instance to read every one of the pastoral poems in order to become familiar with them all, and also to interest their friends in them. In return for these commitments members were offered lifelong membership free of subscription, Members were urged to protect Bloomfield’s birthplace in Honington as well as his house in Shefford and to visit his grave in Campton churchyard whenever they were in the area. Aspirations went much further with the ambition eventually to buy the Shefford house and fit it up as a museum where Bloomfield editions and relics acquired by the society could be treasured. The unveiling of the memorial tablet in Shefford was accompanied with due ceremony. The Shefford fire brigade paraded and afterwards refreshments were promised to the accompaniment of Miss Florence Caton’s playing on Bloomfield’s violin.

How fared this worthy organisation? Whilst the launch certainly did take place, very little is known of the society’s eventual fate and the typescript prospectus which eventually surfaced dates from the time of the Great War. It is easy to moralise on noble ideas that fail but there are two very important legacies in stone of Miss Isherwood’s zeal, both bearing her name in lettering slightly smaller than that of their dedicatee. These are the tablets commemorating the poet at Honington’s church and his house in Shefford; and they have probably done as much as any other physical legacy in perpetuating Bloomfield’s name.

Philip Hoskins

Further reading: see the Bedfordshire Magazine, vol. 23 no. 178 (Autumn 1991).

(Philip is also working on the subject of Joanna Southcott and the Bloomfields and we look forward to a piece on this subject in a future Newsletter, If the [second) Bloomfield Society is less rigorous in its demands on members, hope it will be as enthusiastic as the first. Can anyone supply further information on the fate of Constance Isherwood and her Society?)

Robert Bloomfield’s Bookplate

Bookplates or ‘ex-libris’ as they are sometimes termed, may exert a strange fascination. As with other marks in books, such as marginalia and annotation, they can seem to bring us closer to former owners; telling us something about their beliefs and values. A history of the text lies in its handling.

This awareness of a past physical presence is perhaps all the more intriguing where the owner was in one sense or other a ‘man of letters.’ The plate shown overleaf will be of interest to members for it was designed for Robert Bloomfield, and because it gives a noteworthy insight into the way in which he saw his poetic calling.

Bookplates displaying coats of arms are not uncommon, indeed, by the early nineteenth-century such was the demand that heraldic designs became increasingly standardised as engraving firms sought to cater for an expanding marketplace. However, as Brian North Lee observes in his note on Bloomfield’s bookplate, grotesque heraldry of the sort displayed here is comparatively rare in British bookplates.

Previous commentators have identified two sets of symbols in this engraving, specifically, those drawn from agriculture and alluding to Bloomfield’s fame as ‘The Farmer’s Boy’, and those relating to his background as a shoemaker. The capering figure depicted on the shield, for instance, wears a cobbler’s leather apron and holds a cobbler’s shoe strap and hammer. In addition to these it is worth noting the inclusion of an Aeolian harp and sheet music, plus three books, one of which reads ‘Farmer’s Boy’, in the last quarter of the dexter shield.

Richard Greene has remarked on the way in which that earlier labouring class poet, James Woodhouse, retained a sense of himself as a shoemaker long after he had entered the book trade. Much the same might be said of Bloomfield, and at one level his bookplate might be seen as an unabashed celebration of the idea of a plebeian poet. ‘You are a cobbler. . . and why should you be ashamed of it’, Bloomfield writes in one of the ‘Reflections’ contained in his Remains (II, p. 102).

The bookplate was engraved in 1813 by one W. Jackson of Gutter Lane, Cheapside, and this is perhaps a further indication of the way in which Bloomfield valued his heritage. Those familiar with Bloomfield’s biography will recall that he resided in lodgings in Cheapside during his time as a shoemaker; and it is interesting to see that he retained contacts within this area even after he had left the city.

Sam Ward

Further reading:

The Bookplate Society and The Victoria & Albert Museum, Bookplates in Britain: With references to examples at The Victoria & Albert Museum (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1979).

Brian North Lee, British Bookplates: A Pictorial History (Newton Abbott David & Charles, 1979).

Bloomfield’s Letters

Robert Bloomfield to Joseph Weston, 19 March 1817

Address: Mr Js Weston / Draper / Twickenham / Middx.

Frank: 2 o’Clock / MR 19 / [illegible]

March 19 1817

Dear Sir,

I write with a strangers pen, and with a precipitate hand, just to inform you that, last night I saw Dr Martin and Mr Mariner who both intend to be with you on Sunday next, but Martin will write you more particulars before the time. I intend to be with you by the 2 oclock Coach on Friday.

Love to Miss Weston and Hannah. Yours Sir in good health

Robt Bloomfield

This a short but intriguing letter. In 1810 Clare’s friend Joseph Weston had bought a house in Bedford St., Shefford, Bedfordshire, and this was the house Bloomfield moved to with his family when he left London in April 1812. Mary Philips in her article ‘A Poet at Shefford’, p, 8, says that Weston and his sister Sarah at that time ran a grocer’s and draper’s shop in Shefford, on the corner opposite the Black Swan. By December 1816 they had left Shefford, but continued to take an interest in Bloomfield and his family. At this time Bloomfield was looking for a position for his daughter Hannah, and Sarah Weston found her a place as assistant in a dressmaking business she had started at Twickenham. Robert wrote to Hannah there on 27 December 1816, saying that Weston’s estate had been sold to a ‘boasting hollow lump of worldly cunning’, a man called Mr Demer who was now Bloomfield’s landlord, and a probable source of the poet’s financial difficulties later in his life. By 1817 Hannah had returned home to be with her father.

This letter, then, sees Bloomfield preparing to visit his old friends, and his daughter, in Twickenham. When he says that he writes ‘with a strangers pen’ he can only mean that he has not written recently and so has ‘become a stranger’. What is intriguing about the letter is the reference to ‘Dr Martin and Mr Mariner’, who Bloomfield has seen and who are preparing to visit Weston. Who are they? Well, William Mariner (fl. 1800-60), was a traveller who was, according to the DNB, ‘detained in friendly captivity in the Tonga Islands, 1805-1810’. John Martin (1789-1869) was the meteorologist and London physician who in 1817 (the year of this letter), wrote up Mariner’s story as An Account of the Tonga Islands. I am grateful to my colleague Tim Fulford for identifying these two gentlemen for me, but completely at a loss to explain why Bloomfield and Weston were seeing them. Tim tells me that both Byron and Southey enthused about the Mariner story, and that it must have been a meeting of Bloomfield with ‘another, very different, self-taught writer’. If anyone can cast further light on the meeting, I’d be delighted to know about it. The original letter is reproduced overleaf.

The next Newsletter will appear in Autumn. Please send me any news or other material you would like me to include, I hope to see you on the coach trip or at the seminar.

John Goodridge

************

Newsletter No. 2, November 2001

The lives of labouring-class poets like Bloomfield are often portrayed in terms of what I would call a narrative of failure. Wordsworth applies such a narrative to poets in general (though he is thinking particularly about Chatterton and Burns) in ‘Resolution and Independence’: ‘We Poets in our youth begin in gladness; / But thereof comes despondency and madness’. As far as the self-taught poets are concerned, the statistics seem to support Wordsworth’s rhetoric. There is, for example, a strikingly high incidence of alcoholism, suicide and insanity in the lives of the self-taught poets of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The trouble is that this information tends to dominate our perceptions, overshadowing the many achievements of these poets. One also questions whether the sources are always reliable on these matters. The Dictionary of National Biography says of Bloomfield’s later years that he ‘lacked independence and manliness and would have gone mad had he lived any longer’, an extraordinary statement to find in a major reference book, and seemingly unevidenced. But however cruel and unfair this is (and Ronald Blythe has argued eloquently that it is both), it seems to be part of the way that we habitually think about Bloomfield. We are accustomed to the trajectory of failure. We learn from many sources, for example, that Bloomfield’s poetry declined after The Farmer’s Boy, which is seen as a kind of early benchmark he could never match again. But precisely the opposite could just as intelligibly be argued (and to some extent has been argued, by John Lucas). We might well read the final volume, May Day with the Muses, as the pinnacle of Bloomfield’s achievement in its poetic range and variety, and its ability to incorporate oral and narrative materials into a coherent literary structure. We should, I think, begin to question the ‘narrative of failure’, and I hope that the Bloomfield Society (and the Newsletter) will contribute to this process, Philip Hoskins’s short account of Bloomfield’s life in Shefford, printed below, certainly suggests that a more balanced account of his later life than the DNB offers is now needed. One element in this must surely be a re-appraisal of the story of Bloomfield and the Aeolian harp. His attempts to make and sell Aeolian harps have been widely regarded as ill-judged, part of a wider business and personal failure. But Alan and Nina Grove, who have recently joined our Society, have thoroughly researched this aspect of Bloomfield’s life, and consider that his lifelong devotion to this strange, evocative instrument is a significant event in the history of the English Aeolian harp. It seems, indeed, that Bloomfield may actually have made a crucial design modification to the design of the English form of the instrument. The Groves have spent twenty years making Aeolian harps. They restored Bloomfield’s own surviving Aeolian harp in the Moyses Hall Museum, and have subsequently made reproductions of it as well as modern harps based on the ‘Bloomfield’ design. I have recently interviewed them for the Newsletter, and I shall include this interview in the next number, which will appear early in the new year. I am grateful to Alan and Nina for sparking off this train of thought, and to Philip Hoskins and Simon White for their contributions to this Newsletter. I would again urge people to come forward and contribute information and ideas to the Newsletter, and to Society activities. We need a good variety of contributions to the Newsletter, and ideas for events and activities, if our Society is to thrive.

John Goodridge (editor)

NEWS AND INFORMATION

Bloomfield Society events

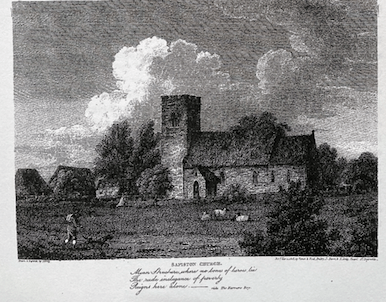

The Society held its first event since the launch last year, on 19th of September, when a couple of dozen members met in Bury St Edmunds to make what was for many of us our first reconnaissance of ‘Bloomfield country’. Unfortunately the Moyses Hall Museum at Bury, where we met, is undergoing extensive refurbishment, so we were unable to see his ‘oak table’ and other materials held there. But we did manage to have a pleasant and interesting tour of Bloomfield country, disembarking from the coach at Honington and Sapiston, and stopping at Troston Hall for long enough to get some impression of Capel Lofft’s home ground. Thanks to the Rector of Honington, the Revd Canon Sally Fogden, we were able to enjoy a number of readings from Bloomfield’s poetry and prose by members in the church at Honington, where Alan Grove also showed us the copy of Bloomfield’s Aeolian harp he has made, and told us a little about this fascinating subject. At Sapiston, where Bloomfield worked as a farmboy, we saw the house of his uncle William Austin (set in a garden surrounded by a haha), and another church – the one whose image is reproduced on the cover of the 1998 Selected Bloomfield – but now frequented (on the day we visited at least) only by a sheltering rabbit. Ronald Blythe, who led our visit, gave us a most interesting commentary on this landscape and its history. I think most of us felt that we had learned a lot about Bloomfield and his world, but there was also a strong sense of resolve for a return visit, to learn more – and perhaps to see the Bloomfield material at Moyses Hall. Many thanks are due to Canon Fogden for her hospitality, to Rodney Lines for organising this event, and to Ronald Blythe for leading it so thoughtfully and interestingly.

We were able to hold our first committee meeting as a Society at the end of the ‘Crossing Borders’ conference in Oxford on 6 July 2001, and a list of the officers of the society, confirmed by this meeting (subject to approval by our first general meeting) is given below, with contact details.

The ‘Crossing Borders’ conference itself, sub-titled ‘John Clare, James Hogg and their Worlds’, was an interesting and important event, which ranged widely over many issues of interest to Bloomfieldians. The organisers, Simon Kövesi and Meiko O’Halloran, are planning to publish the proceedings, and I will keep Newsletter readers informed as to the progress of this project.

Our next event will take place on Wednesday 14 November at Nottingham Trent University (The George Eliot Building, Clifton Campus, Rm, 101), from 5.30-8 pm. There will be a talk on Bloomfield by John Lucas, followed by a discussion and readings by Rodney Lines and others, and the first general meeting of the Robert Bloomfield Society, which will take place from 7-8 pm. (We had hoped to hold this during our trip to Suffolk, but it proved impractical.) Refreshments will be supplied, and all are of course welcome. Apologies for the short notice.

The initial draft outline lettering for a plaque (reproduced below) is only a starting point and options to be considered for the design will include a portrait image and possibly a ‘Farmer’s Boy’ rural scene. Members will have spotted that the quotation is taken from May Day with the Muses which appropriately was written in Shefford. Another important issue is that of finance and when we have estimates of cost we will be turning attention to fund raising.

Philip Hoskins

Robert Bloomfield the Pastoral Poet who is buried in this churchyard

Born Honington 3rd December 1766

Died Shefford 19th August 1823

“Then bring me nature, bring me sense,

And joy shall be your recompense”

NOTES AND ARTICLES

Rural Richness in Shefford

In 1812 Robert Bloomfield came to the little Bedfordshire market town of Shefford to take up the lease of the house in Bedford Road (now North Bridge Street) that he rented from his friend Joseph Weston, and was to be his home until his death there in 1823. He could well have arrived at the Green Man (now the Brewers Tap) opposite the house where incoming carriages would have posted at that time. It is not difficult to imagine the scene. Bloomfield described his new situation in idyllic terms: ‘We have a good house, a middling garden, and a rich country on all sides, every charm of spring surrounds us … a robin is building at our back door, the blackbird sings in the meadow behind, the nightingale is heard even to the doors, the cuckoo plies his two notes all day and a colony of frogs their one by twilight.’ Bloomfield’s mood of optimism was further lifted with the thought that he could live rent free, as the present Duke of Grafton had agreed to continue his father’s pension which would have covered his new rental of £15, an outgoing that was itself less than the £40 a year for his previous house at City Road in London.

With new circumstances problems would arise. Payment of the pension would often need a few genteel reminders and, to generate income, writing had to be put aside for a temporary return to the shoemaker’s last. Declining health challenged not only his creativity but his concerned care for the needs of a growing family, and we can only speculate on the domestic disruption caused by his wife Mary’s involvement with the sect of followers of Joanna Southcott. No wonder that he could come to feel frustration with small town ways and prying. Bloomfield had looked forward to the slower pace of rural society and in 1814 he was able to write: ‘my travels here are of a humble kind, seldom exceeding a nutting expedition or a gossip at the neighbouring farms.’ This was a far cry from his 1807 tour of the Wye. Bloomfield’s celebrity and fame would certainly have preceded him and living close by were the two close friends who had been instrumental in persuading him to come to Shefford: the poetry-loving grocer Joseph Weston and the eccentric watchmaker and amateur archaeologist Thomas Inskip.

He had dined with the local landed proprietor, Sir George Osborn, at his Chicksands Priory home before coming to Shefford. Bloomfield was soon on terms with the pillars of the Shefford community and involved with the comings and goings of the town. His lively account of the feast in 1814 that followed peace with France included a procession, a street party for Shefford’s poor, night long dancing at the White Hart and saw him decorating his house front with the best of them. In spite of declining health in the last decade of his life at Shefford he managed to produce notable work including May Day with the Muses, published in April 1822 just over a year before his death. At that time Shefford only counted for a chapel-at-ease without a consecrated church yard and so he was buried at the church in the adjacent village of Campton some fifteen paces to the east of the east window. The cost of his grave was paid by Thomas Inskip whose own tombstone sits next to it, inclined deferentially in poignant companionship.

Shefford’s development has seen much of its historic architecture chipped away but its early market town character does survive and much of its High Street and the street where Bloomfield lived its shape and much of its character.

Happily many of the public houses that he would have known have survived and amongst these are the Brewers Tap, the White Hart and the Black Swan. These recognisably date from Bloomfield’s time or earlier and can provide refreshment to the follower in his footsteps; but you will have to strain your ears very hard to pick up the song of a nightingale.

Philip Hoskins

Reference: Mary Phillips, ‘A Poet at Shefford’, Bedfordshire Magazine, 57 (Summer 1961), pp. 8-14.

Bloomfield’s Letters (2): ‘the little man’

Most of you will know something about Bloomfield’s dispute with Capel Lofft over the ever-increasing quantity of additional material which Lofft included with The Farmer’s Boy, and his ‘critical’ endnotes in the small octavo version of Rural Tales. The following, hitherto unpublished, letter reveals that the poet’s mind and emotions were still strongly exercised by the dispute four years after it began. He remained worried that some of the ridicule heaped upon ‘the most ostentatious patron of the age’ might have become attached to him by way of association. The letter also helps to explain why Lofft thought that the publishers had turned his poet against him. Finally, and most interestingly, it demonstrates that Bloomfield was not as humble and deferential as his early critics liked to present him, and that relations within the Bloomfield family were not always smooth.

Simon White

Thursday Night

Dear George

The delay of the parcel has enabled me to send you a letter from sister Bet received Thursday in a packet from cousin Isaac to his friends. You say that you and I did not think just alike as to the preface, very likely not. But we thought alike on the subject of Mr L’s eternal additions, and you knew then and was witness in some degree to the dislike of the readers to certain parts of the preface. Of this you and I talked much during the short intercourse we had at Bury and at Honington. I had assured you, as one who would hear it though Mr L would not, that in all companies wherein the subject had been mentioned, the sentiment was the same, invariably the same. I have never seen nor heard the man or woman who speaking of the subject did not applaud his zeal for me, and at the same time either condemn anger, or [ ] his want of judgment, his arrogance, or his vanity: just which they happen’d to hit upon, as in their opinion the most applicable. I have several letters by me from unknown hands abusing him for going too far, in particular for his notes at the foot of the page in the Rural Tales, his ‘simply pleasing’ was to my knowledge a bye word among the young ladies at a boarding school. What ideas they attached to it to make them giggle may easily be divined. I know two high authorities in the Literary world, one of them cut out the notes with his pen knife, and the other would not suffer the copy to enter his library, but destroy’d it when he could procure one that had them not. The former was a friend of CL, and lives at Stamford, and was the same who wrote the Review of my Wild Flowers in the Mirror. I have had conversations with at least a dozen Gentlemen in different lines of connections at Edinburgh who describe the same sentiments strongly expressed there, and as universally as in England. Archer the great Bookseller at Dublin told me the very same tale of the Literati of the sister country, and Stansbury, late a Bookseller at New York gave (voluntarily) the same evidence exactly respecting the people of America, and in the editions of the Rural Tales printed there the notes were left out. I have seen a Gentleman lately from the North of Germany (now in our town) who mentioned to me with peculiar disgust the same hacknied worn out subject. They all cry ‘why dont you tell the man he is doing too much?’ or something to that effect. Now George what does the little man say to me when I would broach this. Why he says, truly, that I have nothing to do with it! There he is egregiously wrong. Does he forget that I have constantly to hear him ridiculed and abus’d and is this nothing? I do not pretend to assert that two years ago you knew just as well as I did how strongly the outcry was against him, but this I assert, that you knew a great deal indeed of it, and therefore when your Note* stated to him that the opposers of him and his tyranny were only a few of the hangers on of that Bookseller with whom you knew he had an inveterate quarrel you did, (I hope) more mischief than you intended. that man would listen to Tom Cat if he could flatter him, so dont pretend that you are too obscure and too humble to be able to do mischief (whether intended or not.) Were I to take it as a risible subject, there is abundance of room for can anyone conceive a poor fellow more universally loaded with hangers on.! There is something in that same of yours respecting Windham, which from [ ] and my own sentiments differ so horribly that I think I shall one day send it you with a few notes, that you may see if I have understood it right or wrong’d you when I deem’d you a turntail and a shufler, and that at a pinch, you would swallow [ ] by pailfulls and glory in the unhappiness you had wrought. Whatever blame you might have heap’d upon Hood at that time (or this) would be sure to be wellcome in Troston. You will perceive by the tone of this letter that it will be well to [send] it me again. I am only speaking in it to you, and send the enclosed to at any time convenient

R. B.

* I have sought in vain for the letter I meant to send, it is in my [ ]. I have no more time

(British Library, Add MS 28268, ff. 216-17, undated but after May 1806)

************

Providence has a very difficult task to please the creature MAN; the latter neglects his proper avocation, Agriculture, to go in search of black eyes and bloody noses, commonly called military glory, and then blames his Maker for not sending him a proper supply of food. – Publican’s Newspaper. (from Bloomfield’s ‘Anecdotes and Observations’ published in The Remains of Robert Bloomfield (1824), II, p. 52)

************

Newsletter No. 3, March 2002

As the Robert Bloomfield Society begins its second year there are now more than fifty members, which is a very encouraging situation. In this Newsletter we have the first of what I hope will be a regular series of readers’ introductions to Bloomfield poems: Hugh Underhill offers a preface to ‘Winter Song’. I have transcribed a conversation I had last year with Alan and Nina Grove, concerning their restoration of Bloomfield’s surviving Aeolian harp, and Bloomfield’s role in the history of the instrument. I have also selected two Bloomfield letters about Aeolian harps to accompany this, to continue our series on his unpublished letters. The more we learn about Bloomfield’s harp-making the more interesting and central to his career it becomes: a link that brings together the craft skills he developed in ladies’ shoemaking, and his interest in poetry and music. I hope that the Newsletter will continue to look at different aspects of Bloomfield’s life and work and reflect his considerable range of interests, and I would renew my plea for members to contribute, perhaps on something that interests them about Bloomfield. I will be happy to consider anything suitable, from a short paragraph to a full-scale essay.

John Goodridge (editor)

NEWS AND INFORMATION

MLA papers on Bloomfield, 2001

The 117th Modern Language Association Convention was held in December in New Orleans, and featured Bloomfield twice. Session 683 on ‘Labor and Romanticism’, chaired by Kevin Binfield of Murray State University, included a paper by Tim Burke on ‘National and Poetic Identities in Bloomfield’s “The Banks of Wye”‘. Session 549, arranged by the John Clare Society of North America and chaired by John Coletta of the University of Wisconsin, was entitled ‘Clare and Bloomfield: Romanticism, Influence and Material Culture’. It included a paper by Bruce Graver on ‘Bloomfield in America’, and my own paper on ‘Female Storytellers in Bloomfield and Clare’. The MLA is the largest annual academic event in the field of literary studies. It is surely unprecedented to find Bloomfield in two sessions, and certainly very good news for Bloomfield studies on both sides of the Atlantic.

We were sorry to learn of the death of one of our first members, Mr W. T. Farrer of Edinburgh. Mr Farrer was also a dedicated member of the John Clare Society, to whose archive he had contributed several items. We extend our warmest sympathies to Mrs Farrer.

The book of essays on Bloomfield I mentioned in the first Newsletter is coming along well. Most of the contributions are now completed and gathered in, and I have joined Simon White as co-editor of the collection. Negotiations with publishers are continuing, and we hope to be able to publish it soon. I’ll keep members informed about this.

It is nice to be able to report that there is a well-established bookshop whose antiquarian specialisms include Bloomfield and Suffolk authors: this is Claude Cox books of Ipswich.

Bloomfield Society activities

We held our first Annual General Meeting at Nottingham Trent University on 14 November 2001. John Lucas began the evening with a well-received and splendidly anecdotal talk on what drew him to Bloomfield. This was followed by a series of readings and discussion of Bloomfield texts by members of the Society (Hugh Underhill’s introduction and reading of ‘Winter Song’ was a highlight, and formed the basis for his article, printed below). The AGM itself got through quite lot of business, confirming the Society’s Constitution and Officers, and planning out some future events and activities. (Full minutes of the meeting will be circulated to all members.) This was the second time we have met at Trent. It was again an enjoyable occasion, and we decided to continue holding our AGMs at Trent. This year’s AGM will be held on Wednesday 13 November 2002. As before, it will be held in the George Eliot Building, Clifton Campus, and will begin with informal readings and discussions from 5.30 pm. Refreshments will be provided, and all our members are very welcome to attend.

Arrangements for our summer event are not yet settled, but Tim Burke is working on an event based in or around ‘Bloomfield’s London’, probably in late summer, and we shall have more details of this in our next Newsletter. We also hope in the future to make a return trip to Bury St Edmunds and ‘Bloomfield Country’, and to visit Shefford, and Campton Bloomfield Monument – Campton Church. Ideas for the proposed Bloomfield monument in the church, commemorating his interment in Campton’s churchyard, took firmer shape at a meeting of joint representatives of the Bloomfield Society committee and Campton’s Parochial Church Council on 14 February 2002. This ad hoc sub-group reviewed preliminary design sketches and felt that the plaque should include not only particulars of Bloomfield’s date and place of birth and death, as well as a quotation from his works but also ideally a side-profile of the poet and some emblem such as an ear of corn representing nature. Happily a very suitable position for the monument exists in the nave of the church on its south wall. The next aim will be to approve a suitable artist to handle the project. We have one eminently suitable candidate but hope to hear from at least one potential alternative. Thereafter we will be able to canvass for suitable financial sponsors. We are assuming that a total of up to about £5,500 will be required (and if any members might seriously aspire to a unique and lasting recognition with a supreme act of literary benevolence please contact Philip Hoskins). The process of securing approvals – not least from the church diocesan authorities – will probably be lengthy, but we intend to end up with a memorial that is worthy of the poet’s artistic achievement and a fitting embellishment to the church.

Philip Hoskins

NOTES AND ARTICLES

An Introduction to ‘Winter Song’

Hugh Underhill

The opening line of this ‘song’ (printed below) may call to mind ‘When icicles hang by the wall / And Dick the shepherd blows his nail…’ and the two seasonal songs to which it belongs at the end of Love’s Labours Lost, but Bloomfield needed no prompting from Shakespeare. In the rural world he is remembering from his boyhood there would have been ready access to a store of ‘season’ songs and poems, a traditional popular ‘kind’ rooted in an agricultural way of life governed in all its aspects by the seasons. And Bloomfield at his uncle Austin’s farm might well have been such a boy being told, kindly, to get back to his task of snow-clearing instead of larking about (if this is what he is doing) with ‘that Icicle’. Versions of the anapaestic line he uses (compare his ‘Song, Sung by Mr. Bloomfield at the Anniversary of Doctor Jenner’s Birth-Day 1803’) are common in popular song and poetry (‘Come, lasses and lads, get leave of your dads…’). Smoothness is not a priority and iambs, inversions etc. might be mixed in, but the heavy-stressed rhythm, with the lines fixed in place by regular rhyme, is an obvious aid to memory. The poem testifies, then, to popular and oral traditions in a world, as we see at lines 17-20, where news was still carried by word of mouth. A range of traditional and commonplace topics, the ‘oft-expressed’ in learned as well as popular works, is touched on here: the sufferings of the poor in hard times, against which are set the unfeelingness of pomp and wealth (lines 4-8, 29-32); the duty of hospitality, which among the labouring classes seems more a spontaneous sharing of warmth and shelter and whatever one has in winter (lines 9-12, 25-8); the power of true affections to be proof against time (lines 13-16); modest comforts bringing a contentment often denied the great (lines 23-4). But as so often, whether in theme or choice of form, Bloomfield profits from traditions while bringing something distinctively his own to them. A commonplace like ‘Time may diminish desire, / But cannot extinguish true love’ doesn’t seem one here; it affects us, I think, as something directly felt. Such effects are achieved by the lived immediacy of setting and detail, the homely expressions, the freshness and ease of voice (Dear Boy…’). It’s also a matter of pitch, of something equable and unforced, a certain delicacy which wins our trust. The speaker doesn’t seem striving for profound reflections but saying straight out what he feels and values. The poem echoes much that Bloomfield affirms in The Farmer’s Boy and elsewhere, celebrating ‘natural affections’, the feelings and generous impulses on which community depends and which sustain domestic life. The quiet wit of his concluding play on notions of wealth and poverty suggests more. These lines might appear too ready to acquiesce in a given order and the acceptance of a mean lot (as might, for example, parts of May Day with the Muses). But attention to the precise thought of the lines and to the weight of ‘fool’ and ‘slave’ (perhaps also to a sub-text about the amassing of fortunes from mining enterprises while the poor languish), impresses us with Bloomfield’s fixed resolve in that holding to ‘conscience’ and in the reproof to those who pursue riches and refinement at the cost of humanity. He may have located such values in a lost world but they never lost their force for him.

WINTER SONG

I.

Dear Boy, throw that Icicle down,

And sweep this deep snow from the door:

Old Winter comes on with a frown;

A terrible frown for the poor.

In a Season so rude and forlorn,

How can age, how can infancy bear

The silent neglect and the scorn

Of those who have plenty to spare?

II.

Fresh broach’d is my Cask of old Ale,

Well-tim’d now the frost is set in;

Here’s Job come to tell us a tale,

We’ll make him at home to a pin.

While my Wife and I bask o’er the fire,

The roll of the Seasons will prove,

That Time may diminish desire,

But cannot extinguish true love.

III.

O the pleasures of neighbourly chat,

If you can but keep scandal away,

To learn what the world has been at,

And what the great Orators say;

Though the Wind through the crevices sing,

And Hail down the chimney rebound;

I’m happier than many a king

While the Bellows blow Bass to the sound.

IV.

Abundance was never my lot:

But out of the trifle that’s given,

That no curse may alight on my Cot,

I’ll distribute the bounty of Heaven,

The fool and the slave gather wealth:

But if I add nought to my store,

Yet while I keep conscience in health,

I’ve a Mine that will never grow poor.

Note: ‘at home to a pin’ (line 12). Francis Grose’s 1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue has:

In or to a merry pin; almost drunk: an allusion to a sort of tankard, formerly used in the north, having silver pegs or pins set at equal distances from the top to the bottom: by the rules of good fellowship, every person drinking out of one of these tankards, was to swallow the quantity contained between two pins; if he drank more or less, he was to continue drinking till he ended at a pin: by this means persons unaccustomed to measure their draughts were obliged to drink the whole tankard. Hence when a person was a little elevated with liquor, he was said to have drunk to a merry pin.

Bloomfield & the Aeolian Harp: A Conversation with Alan & Nina Grove

John Goodridge

Alan and Nina Grove have been making musical instruments for many years. They restored the only known surviving Aeolian harp made by Robert Bloomfield (in the Moyses Hall Museum, Bury St Edmunds), and have since made many ‘Bloomfield harps’ – precisely crafted modern replicas of the original. They are members of the Bloomfield Society.

John: How did you first get involved in Aeolian harps?

Alan: We were already involved in building clavichords and harpsichords. I was working on a clavichord commission, and happened to have the radio on, and there was a programme about someone who made an Aeolian harp. I fancied I had heard one in the past, but all I knew was that the moment I heard this sound coming over the radio, I knew the sound, and it was so incredible, and I was so absolutely overwhelmed with the whole idea of an instrument that played itself in the wind, that I thought, well I’m going to make one of these, you see. So I actually set aside my commission, and we built our first Aeolian harp instead, purely by knowledge of one instrument transferred to another. We took it to Suffolk and played it in the open (this was quite a large Aeolian harp, measuring about five feet long). We had learned that there was an Aeolian harp made by Robert Bloomfield in Moyses Hall, and we were going to see that at the same time.

John: Did you know anything about Bloomfield then?

Alan: No, not a thing.

Nina: How did you know they had got one in Moyses Hall?

Alan: From Stephen Bonner, who had written his university thesis on the subject of the Aeolian harp, and published it.* He himself had been all over Europe sussing out original instruments in museums – which included the Moyses Hall one. Anyway, we got to Moyses Hall, and found this instrument on a table, literally in pieces. I mean, there it was, there was the body of the harp. The lid had a spurious triangle of wood on the underside, which propped it up for viewing. But that was how we found it – no strings, no bridges, no support blocks on the lid. So we had to measure it up, and do some research as to how this thing would have looked, as Bloomfield left it. And the then curator suggested that we restored it. Nina I think he felt sorry for us, because we were making such a lot of notes, and getting worried about time. He said, oh for goodness sake, borrow it!

Alan: He said, would you restore it for us? So I said, well if you allow us to get the wood analysed, and if you give us a free hand, and allow us to have it for, perhaps a year, six months or a year, then we’ll restore it free of charge – and then can we make replicas of it commercially? So that was agreed. But there was nothing to put it in, so he found a potato sack in the store and just popped it in, and off we went, having signed an affidavit to bring it back by a certain deadline.

John: Do you know where they got the harp from, how it came to them?

Alan: Yes, it was donated to the museum by a Mr Harold M. Boniwell of Bury St Edmunds, in 1953. The inscription on the lid shows that it was made by Bloomfield for Capel Lofft, with the date, 1808. Boniwell ran a music shop in Bury St Edmunds, and presumably someone had turned up at the shop with it. We have since heard of a second Bloomfield Aeolian harp, which is now lost, this one reported to us by Robert Ashby, the editor of Bloomfield’s letters. Ashby walked into Moyses Hall museum one day, sometime after I had restored the instrument. It had now become quite a display, because the curator had got me to produce drawings of how the instrument was played in the sash window, and a little bit of information about Bloomfield – quite a nice little display which, from being just a wreck on his round oak table, was now a proper display taking quite a lot of space in Moyses Hall. That’s since been cut back a little bit. But the harp has been around: it went to the States, it went to Chicago.

John: How did you begin to restore it?

Alan: Well, there we are with the instrument in a potato sack. It was a very hot May day, and the harp was in the back of the car. It was getting so hot that I took it out of the car, took it out of the potato sack to get air round it. The moment I lifted the harp out of the sack, I heard a rattle, and somehow guessed what this rattle might be. We had no bridges, and even though we had hitchpins and tuning pins still in position, we had no idea of the spacing of the strings, which is very critical to the way an Aeolian harp performs. So I got it to drop out of the sound hole, and there was a bridge. It had some sticky resin on it, and I assume it had got attached to the inside of the harp, and had come loose in the heat. This was very exciting, as it was quite clearly an original bridge, because it had warped due to string pressure, and the bottom fitted the warp of the soundboard precisely. So what remained to be done was to make a replica of that one bridge, and we marked it on the underside as a replica. The next problem was what the cover support blocks were like, and this was more difficult. We had some idea of their position, because there were four locating holes in the soundboard of the harp, where the lid pegs fitted. What we had was the body of the harp – the soundbox, the hitchpins and the tuning pins and the lid, but no remains of stringing. When Stephen Bonner had photographed it for his book, there were clearly remains of gut strings, and this would have been very useful to work out the string diameters. But that wasn’t unsurmountable. We knew the position of the bridges, because there were quite clear marks on the soundboards. (The bridges on a harp are loose, like a violin.) An interesting thing is that in one of Bloomfield’s letters – I think it is to Capel Lofft – he talks about a development. He had discovered something which he considered quite a development in the design of the Aeolian harp, which he considered was going to improve the resulting sound. And I think – I can’t prove this but I think – that what he discovered was that if you slope the soundboard, and then place the instrument in the sash window, then once you had got the cover in place, you then get a funnel effect. You have got a wider opening at the front, and what we do know is that there isn’t any example of an Aeolian harp with a sloping or inclined soundboard before Bloomfield.

John: What documentation is there of the history of the Aeolian harp? Is there any evidence there?

Nina: Quite a bit really. Not about Bloomfield particularly, but there is about other people.

John: But is there any evidence as to how it got that sloping soundboard?

Alan: No, except what Bloomfield hints at.

John: You say he discovered something. Does that mean he discovered by experimenting himself?

Alan and Nina: We think so.

Alan: He was a great experimenter, we know that.

Nina: He may well have experimented with strings. He would know about gut because of his shoe trade. But some people were trying silk, and metal wires.

Alan Bloomfield experimented with silk. He wasn’t much impressed with that. He wasn’t actually much impressed with the idea of a cover on an Aeolian harp anyway, because as we have found ourselves, it isn’t much of an aid. The idea of the cover originally was to provide the right gap … The Bloomfield harp, which measures 34 inches or thereabouts overall, fits a three foot Georgian sash window nicely. In fact we know that the original harp fits the rear windows of Troston Hall perfectly.

John: You’ve been there with a tape measure?

Alan: (laughs) Yes, we actually put the harp in the window, so we know that the Bloomfield harp at Moyses Hall, which was dedicated and given to Capel Lofft as a present in 1808, fits his window.

John: Fantastic!

Alan: But Bloomfield must have been quite commercially minded as far as his Aeolian harps were concerned.

John: I was going to ask you about this. The standard view is that he was a failure at making Aeolian harps, that he couldn’t make it pay, or he couldn’t make it work. And I’ve always been suspicious of that.

Nina: I think it is the opposite really. I think it kept him going.

John: You think he was a successful Aeolian harp maker?

Alan: Yes.

John: Well you have already told me so, in terms of the design. And the fact that you are making something you are calling ‘Bloomfield’ Aeolian harps and selling them, seems to me quite good evidence of his success. But I wonder about the way it is discussed as if it were some failed enterprise that he tried to do.

Alan: Well from our own experience – we have a very big collection of antique harps, which we have built up since we restored the original Bloomfield harp. We now have in excess of 25, including now – which is very exciting – the oldest dated Aeolian harp there is, which precedes the Bloomfield (and, interestingly, doesn’t have a cover). It was made by William Banks the Salisbury violin-maker, and dated 1787. This is the oldest English Aeolian harp, and probably the oldest dated harp in Europe. The Bloomfield harp was our first experience of a working English sash-window Aeolian harp, so we had no means of making comparisons. Now that we have this big collection we are excited by the fact that the Bloomfield is still the best. It is still the easiest to play. It still makes the most beautiful music. I would suggest that if there was any dissatisfaction with Bloomfield’s Aeolian harps, it was probably by virtue of the fact that the purchaser didn’t really know how to use them, or how to set them up. We have set up an Aeolian harp for a customer, and it took twelve months for them to get a tune out of it! There was nothing wrong with the harp, just the situation it was in. If we look at the sale of Bloomfield’s effects at his house in Shefford in 1824, we note that there were six unfinished Aeolian harps, and that suggests that he was still very actively involved in making Aeolian harps, possibly right up to his death. We don’t exactly know how many he made, but we think that it was quite a big commercial venture.

Top: Bloomfield’s 1808 Aeolian harp, restored by Alan Grove, now at Moyses Hall Museum, Bury St Edmunds.

Bottom: ‘Bloomfield’ Aeolian harp, made by Alan Grove as a precise modern replica of the 1808 harp. It is decorated with a left profile of Bloomfield, and lines from his poem ‘Aeolus’: ‘Be true, sweet harp; hush all but thee: Perform thy task untouch’d, alone’.————————————–

John: I think you said to me when we talked last time that he was interested in Aeolian harps from quite an early stage?

Alan: There doesn’t seem to be any interest before 1800 – maybe 1798. Letters refer to them from about 1800, and we think this was when he started making these things commercially.

Nina: Who did he see, or who did he mix with to know about them?

Alan: He would have read all the poems that referred to the Aeolian harp.

John: Well certainly, by the time he came to publish Nature’s Music in 1808. But Bloomfield had a lot of contacts, didn’t he? He lived in London, he was a big success after The Farmer’s Boy came out – people would have sought him out. We know from the letter I put in the first Newsletter that he knew Dr Martin and Mr Mariner. They were celebrities at that time – so what’s Bloomfield doing mixing with them? Presumably he mixed with a lot of different people.

Alan: And Edward Jenner, of course.

John: Yes. Bloomfield was for a while an important person, a celebrity himself. He was the bestselling poet of the time. So I would imagine he would have made all kinds of contacts. There is also – I am speculating – the possibility that there would have been some connection through craft, through his profession as a ladies’ shoemaker, with instrument makers.

Nina: Aeolian harps were already popular, very popular at the time.

Alan: Well Clementi, whose outworker decorated the harps for Bloomfield, must have been taken up with this idea. Most of these publishers-cum-piano makers were. Charles Humphries and William C. Smith’s Music Publishing in the British Isles (1970) lists all the music publishers and musical instrument makers, and most of them did both.

Our conversation digressed at this point, and only briefly returned to Bloomfield. I learned a great deal more about Aeolian harps, their construction and tuning, and heard some of the strange, ethereal music they produce, a music in which, according to Alan and Nina, you can sometimes hear snatches from Bruckner or Berlioz (apparently many of the great composers used and were inspired by these instruments). Alan and Nina continue to research into and build Aeolian harps, and pursue their interest in Bloomfield’s role in their history. A full report on the restoration of the Moyses Hall harp is lodged in Suffolk Record Office, Bury St Edmunds.

* Stephen Bonner (ed.), Aeolian Harp (Duxford, Cambs.: Bois de Boulogne, 1968-74):

Vol. 1. The design and construction of an Aeolian harp, by Jonathan Mansfield (1968).

Vol. 2. The history and organology of the Aeolian harp, by Stephen Bonner (1970).

Vol. 3. The Aeolian harp in European literature, 1591-1892, by Andrew Brown, with additional material by Nicholas Boyle (1970).

Vol. 4. The acoustics of the Aeolian harp: supplement to volumes 1-3, by Stephen Bonner and M.G. Davies, line drawings by Vic Woodward (1974).

Bloomfield’s Letters (3): ‘aeirial music’

John Goodridge

Here are two Bloomfield letters about his Aeolian harps. The first is to a William Russell, dated from the postmark 5 December 1807. Of the four William Russells in the Dictionary of National Biography who were alive in 1807, the most obvious candidate is William Russell (1777-1813), ‘musician; organist to Great Queen Street Chapel London’ who ‘composed sacred music, songs and theatrical pieces’ (Concise DNB). From this letter we learn that Bloomfield had his harps decorated by a craftsman in Goswell Street (probably modern Goswell Road), whose understandably higher priority was to complete outwork for the great Italian composer and rival to Mozart, Muzio Clementi (1752-1832). Clementi had been encouraged to come to England as a young man, and having enjoyed a successful career as a pianist and composer, set up his piano-making workshop in Cheapside, the principal street in London for instrument making in the period. We also learn from the letter that it is not only difficult to get your Aeolian harps finished on time, but also to get music out of them at all, with the result that the customer was sometimes unsatisfied, as evidently is the case here. The second letter is to James Montgomery (1771-1854), poet and radical editor of the Sheffield Iris, a key literary figure with many connections to labouring-class poets like Bloomfield and Clare. He is also treated to the familiar Bloomfieldian catalogue of woes, but is also given some interesting advice on setting up the harp, and on the subject of strings. There are other references to Aeolian harps in Bloomfield’s letters, for example Capel Lofft, for whom he made the Moyses Hall harp in 1808, had written to him two years earlier saying that ‘This instrument has been always a great favourite with me and with Mrs. Lofft’ (Letter 41 in Hart’s edition).

I am grateful to the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge, for kind permission to print the first letter, to Alan Grove for information on Clementi, and to Sam Ward for rediscovering the Montgomery letter, which was first published in 1855.

Robert Bloomfield to William Russell, 5 Dec 1807 (Trinity College Library, Cambridge, MS Cullum k26(2))

City Road [5 Dec 1807]

Mr Wm Russell

I am conscious that my conduct may appear to you extremely unhandsome and, I feel somthing like uneasiness until I explain. I am in the habit of making the instruments with my own hands, but inscribing my name and a slight ornament, which is done by a man in Goswell Street. When you call’d, I was to have your Harp and another home in a day or two, but was disappointed and obliged to give way to one of his better employers, Clementi in Cheapside, who hurried him with Drums, going abroad. He finishd many of my Harps during the last Summer and I never felt the disappointment before. They are half done, and set by; and, I have now certainty of getting them on Monday next. We have had very uncongenial weather lately for aeirial music, but I beg you to remember, Sir, that if by your change of abode the Harp in dimensions becomes wrong, you are at liberty to change it at a future time, if undefil’d. You shall find it at your Brother’s very shortly. After this apology need I add that, I am sorry every way for your disappointment And hope that your experiment and entertainment from the Instrument will answer your expectations,

Yours, Sir truly

R Bloomfield

Robert Bloomfield to James Montgomery, 26 May 1809 (from John Holland and James Everett, Memoirs of the Life and Writings of James Montgomery (London, 1855), II, pp. 209-10)

London, May 26. 1809

Dear Sir,

Upbraid me not, if you can help it, for my extreme tardiness. I have had some of the world’s cares to buffet with, – a long and severe rheumatic winter, and a total privation of the strength and resolution to attend to music or poetry; – add to this, my son with a broken leg, which, considering it was that which had been long lame, and must continue so, has been as far restored as reason could crave. He is well, and his father is alive again.

You know the nature of the instrument I send, and therefore I only observe, that if when placed under the lifted sash, or just inside, so as to conduct a current of air through the strings, it should not play satisfactorily, then take off the top board and place the harp alone on the broadest edge with the strings rising nearly perpendicularly over each other, and close to an inlet made by lifting the sash about an inch. I have no doubt that it will perform; but I should be glad to hear of any intimations to that effect, at any convenient time. I have been informed that you too have been out of health, or spirits, or both, – I know not which, but hope to hear a good account.

Your harp, I doubt, is too short to admit of larger strings; but you may possibly enjoy quite as much the extreme softness of the smaller ones: that you may, is my hope: and that you may find some amusement from a thing so frail, and not suffer it to be a ‘Harp of Sorrow,’ is my ardent desire. What is your Muse about? will not this delightful season set you a-going again? Whether it does, or not, I remain, Sir, Your humble servant,

Rob. Bloomfield.

Barry Bloomfield (1931-2002)

I was very saddened to learn, as I was completing this Newsletter, of the death of our member Barry Bloomfield. Barry was widely respected as the bibliographer of Larkin and Auden, the centenary president of the Bibliographical Society, and a key figure in the library world. He was also a descendant of the poet’s family, and his essay on the publication of The Farmer’s Boy is still the best piece of Bloomfield scholarship I know. When John Lucas and I were doing our selection of Bloomfield a few years ago he helped us most generously, and he and his wife Valerie made us welcome when we visited them. He had some wonderful Bloomfield editions, and an anecdote or an insight to go with each one we looked at. Such a combination of generosity, wit and wisdom is rare, and we shall miss him. There are obituaries in The Independent (2 March 2002) and The Times (6 March). JG

************

Newsletter No. 4, July 2002

Following the bicentenary of The Farmer’s Boy in 2000, we are now in the bicentenary year of Rural Tales, Ballads and Songs (1802), not an anniversary perhaps noted by many, but important nevertheless. Bloomfield’s second volume begins to develop a more popular style of narrative and song-based poetry. Together with what we could call his ‘conversational’ poems, this would become the strongest area of his mature verse. The conversational style is represented in Rural Tales by ‘The Widow to Her Hour-Glass’. The narrative style is seen in half a dozen of the longer pieces, including the holiday ballad ‘Richard and Kate’, and ‘The Fakenham Ghost’, a false-ghost story of a familiar type. Crossing over from polite poetry to the folk tradition, Bloomfield names many of the poems ‘ballad’ or ‘song’. (One of the best of them, ‘Winter Song’, was discussed by Hugh Underhill in the last Newsletter.)

Rural Tales was evidently a successful volume, because it was separately reprinted a dozen times in its first decade, as well as back-to-back with The Farmer’s Boy in the various early editions of Bloomfield’s Works. Looking at some of these early printings, which have less delicate, more graphic styles of illustration than The Farmer’s Boy, one gets the impression that this volume might have sold to a more popular readership. At any rate Bloomfield pressed on with verse stories in his third collection, Wild Flowers (1806). This was less popular in sales terms, but contains two of his most striking narrative poems, ‘The Horkey’ and ‘The Broken Crutch’. ‘The Horkey’ uses dialect and humour to create a more raucous holiday poem than the gentle celebration of family values offered by ‘Richard and Kate’. ‘The Broken Crutch’ is a melodrama with a plot Thomas Hardy might have dreamed up. Bloomfield’s final exercise in narrative poetry was the most ambitious: May-Day with the Muses (1822), which attempts a full-scale storytelling festival with a framing narrative in the manner of Chaucer or Boccaccio. It is a mystery why this fine poem was so miserably received, and remains little-known. The bicentenaries of Bloomfield’s later collections, this year and in 2006 and 2022, should at the least provide a good opportunity to look again at these volumes, and discover some of the forgotten treasures that they contain.

John Goodridge (editor)

NEWS AND INFORMATION

‘London market, London price’

The Bloomfield Society ‘field trip’ this year will be to Bloomfield’s London. This will be on Thursday 19 September, led by Dr Tim Burke of St Mary’s College, Strawberry Hill. The draft itinerary is as follows:

Meet at City Road near Bloomfield’s house

Walk or bus to Paternoster Row & environs – Bloomfield’s publisher

Cross the new Millennium Bridge and go by train to Shooter’s Hill (picnic or pub lunch). Return to St Pancras Tour of the British Library in St Pancras including seeing Bloomfield’s manuscripts.

Drinks at a (Bloomfield-related?) pub somewhere near the BL.

I do emphasise draft itinerary. At the time of writing, Tim is in negotiation with the British Library over timing and numbers. He is also poring over bus and rail timetables trying to find relatively painless, inexpensive ways to move round London. It appears it will cost £5 per head for the BL tour, and there will be our transport costs to add to this. But this promises to be a pleasant and not too expensive way of seeing something of Bloomfield’s life in the city he described as follows (just to whet our appetites):

Provision’s grave, thou ever-craving mart,

Dependant, huge Metropolis! where Art

Her poring thousands stows in breathless rooms,

Midst pois’nous smokes, and steams, and rattling looms.

Where Grandeur revels in unbounded stores;

Restraint, a slighted stranger at their doors!

Thou, like a whirlpool, drain’st the countries round,

Till London market, London price, resound

Through every town, round every passing load,

And dairy produce throngs the eastern road... (‘Summer’, lines 237-46)

Please contact Tim Burke if you would like to go to this event, or to find out more about it.

George, John and Ada

This year’s annual general meeting of the Bloomfield Society, as I mentioned last time, will be on Wednesday 13 November 2002. As before, it will be held in the George Eliot Building, Clifton Campus, Nottingham Trent University, starting with informal readings and discussions from 5.30 pm. Refreshments will be provided, and all are very welcome to attend. Incidentally, we have a new lecture-theatre building at Trent, opposite the George Eliot Building, and next to the Ada Byron King Building, and the university has recently agreed to name the theatres after John Clare. (It seems especially fortuitous to have Clare between Byron’s daughter and the author of Scenes of Clerical Life (and Middlemarch, not long ago filmed in Clare’s Stamford). But if they put up any more new buildings, I’ll certainly put forward Bloomfield’s name...

One piece of good news on the book of Bloomfield essays Simon White and myself are preparing: Barry Bloomfield’s checklist of Bloomfield editions was completed before he died and will be included in the volume: a small but valuable consolation for a very great loss.

Lastly, a reminder that contributions from members will be very gratefully received; not just articles, but notes, questions, thoughts, personal and creative responses, illustrations, and useful information of all kinds. Thanks to Philip Hoskins for another interesting piece, and to Tim Burke for valuable help in decoding the Bloomfield-Rickman correspondence. JG

Around Bloomfield’s Wye

Philip Hoskins

‘In the summer of 1807, a party of my good friends in Gloucestershire, proposed to themselves a short excursion down the Wye, and through part of South Wales.’ Thus begins the preface to Bloomfield’s poem The Banks of Wye; it also introduces my own account of a brief pilgrimage this year, in an exceptional week of fine April weather, to retrace Bloomfield’s route on his celebrated tour. Armed with his poem and his prose journal we had no need for a modern guide book.

Bloomfield’s itinerary took him from Uley in Gloucestershire, across the Severn at Framelode and then through the Forest of Dean to Ross on Wye. From there the party travelled by boat to Monmouth and then continued on the river via Tintern Abbey to Chepstow. In their two carriages, appropriately named sociables, they drove on through Raglan, Abergavenny, Brecon, Hay-on-Wye, Hereford, Malvern and Tewkesbury before ending back at Uley.

The map of their journey was dominated by rivers and peppered with border castles like Goodrich, Chepstow, Raglan and Abergavenny that were already tourist sites, albeit often decayed, in Bloomfield’s time. We dipped into some of the other curiosities that drew the poet’s attention including Tintern Abbey where the party took time to breakfast and paint while Bloomfield sang Psalm 104. Not having a copy of the psalms with me and thinking it more fitting anyway I recited the first few lines of Wordsworth’s ‘Tintern Abbey’, more or less accurately remembered.

In our journeying, we found no castles more enjoyable than Clytha Castle, a Landmark (in reality owned by the National Trust) property between Raglan and Abergavenny that we had rented as our holiday base. This was an elegant folly constructed with rounded towers on a promontory overlooking the old road that Bloomfield’s sociables must have trundled along. As a plaque on the main wall of the castle records: ‘Erected in 1790 by William Jones of Clytha House, husband of Elizabeth, last surviving child of Sir William Morgan of Tredegar, it was undertaken with the purpose of relieving a mind afflicted by the loss of a most excellent wife’. Many of the visitors’ comments in the log book mentioned the spookiness of the castle, but we waited in vain to greet the peerless Elizabeth in the silent hours.

One of the features of Landmarks is that you (or perhaps your wife as in our case) have to handle the commissary for your temporary residence which, like Bloomfield’s pleasure boat, needed copious ‘provisions and bottles &c &c &c’. We found all we needed at Abergavenny on market day where we joined the crowd that expectantly descended on it from Welsh border towns and villages within range as they would have done in past centuries.

We were following the trail not only of Bloomfield, but also of the metaphysical poet Henry Vaughan who lived for most of his life at Newton near the River Usk between Abergavenny and Brecon. Bloomfield’s itinerary was crossing into Vaughan’s preserve when he and his party visited Tretower Castle which, with the nearby Tretower Court, was part of Henry’s family patrimony even if his father was denied inheriting it through the laws of primogeniture.

Tretower Court is a large complex of living rooms, kitchens, gatehouse, hall and store rooms, adapted to meet the tastes of successive owners from its construction in the 14th century onwards. Although now sparsely furnished it is easy to imagine all the buzz of domestic life that must have gone on within its walls in mediaeval and Tudor times.

After being confused by Welsh place names and going to the wrong church, we found at Llansantffraed’s churchyard overlooking the Usk the massive stone headstone recording Henry Vaughan’s death in 1685. The headstone was brightened by a circlet of fresh yellow flowers placed there by the Brecknock museum in respectful memory of Vaughan. It is a spot well described by Siegfried Sassoon in his sonnet ‘At the Grave of Henry Vaughan’:

Above the voiceful windings of a river

An old green stone of simply graven stone

Shuns notice, overshadowed by a yew.

After calling at Hay and again joining up with the Wye it was time to quit our tour and go home leaving the last part of the route unfinished as a must-not-forget reminder to return. As we left it was again a few lines by Vaughan about his beloved Usk that were uppermost in our minds and seemed to speak just as clearly for Robert Bloomfield’s Wye:

Poets (like Angels) where they once appear

Hallow the place, and each succeeding year

Adds reverence to’t, such as at length doth give

This aged faith, that there their genii live.

(From ‘To the River Isca’)

Bloomfield’s Letters (4): ‘I rejoice in your profanity’

John Goodridge

This is an interesting, slightly edgy exchange of letters between Robert Bloomfield and Thomas ‘Clio’ Rickman, bookseller and radical, best known as the biographer and friend of Tom Paine. Bloomfield wrote to Rickman at the end of May 1804, enclosing a letter and half a guinea, the latter in payment for books Rickman’s shopboy had left and ‘for the former 4 copies of the Letters’. He mentions recent events in Domingo, professes himself a ‘cowardly’ neutral in matters of political and religious controversy, but nevertheless makes some sharp comments on Paine and republicanism. A postscript mentions a ‘small thing just published’ which is ‘too large for the post’. Rickman replies the next day, warmly complimenting his correspondent while defending Paine, all in the slightly overblown style that had perhaps helped to form his reputation for literary precocity. Both men had recently published books. Bloomfield’s mention of Domingo would strongly suggest that one of the ‘Books your Lad has left lately’ was Rickman’s own poem, An ode, in celebration of the emancipation of the blacks of Saint Domingo, November 29, 1803 (1804). Bloomfield’s ‘small thing just published’ was his poem on smallpox vaccination, Good Tidings; Or, News from the Farm (1804), a work of medical triumphalism to match Rickman’s political celebration. It is not obvious what the letter that ‘came in a packet’ from Capel Lofft might have been. Lofft had written in haste on 9 May, making final suggestions for ‘Good Tidings’ and discussing literary matters (nothing of obvious interest to Rickman). The ‘4 copies of the Letters’ Bloomfield has earlier received and is paying for along with the new books are also a puzzle. Rickman’s own Letter addressed to the addressers, on the late proclamation (1792) seems a bit remote. A more promising candidate is the Letters of the late Ignatius Sancho, an African: to which are prefixed memoirs of his life by Joseph Jekyll. The fifth edition had been published in London the previous year, and these letters are alluded to in Rickman’s opening sentence. It may be ventured, then, that Bloomfield was taking an interest in slave emancipation and black culture – and perhaps sharing these interests with others, if he indeed had ‘4 copies’ of Sancho’s book. This would certainly all tally with Jonathan Lawson’s remark that ‘Bloomfield’s character in 1804 was, despite his financial difficulties, that of an independent, confident man’ (Robert Bloomfield, Boston: Twayne, 1980, p. 31).

Robert Bloomfield to Clio Rickman, 29 May 1804

(British Library, manuscript RP 4250, by permission of the British Library)

Shepherd & Shepherdess City Road

May 29th 1804

To Mr Rickman

Sir, The enclosed letter came in a packet from Mr Lofft.